How Transformer Models Detect Anomalies in System Logs

Table of links

Abstract

1 Introduction

2 Background and Related Work

2.1 Different Formulations of the Log-based Anomaly Detection Task

2.2 Supervised v.s. Unsupervised

2.3 Information within Log Data

2.4 Fix-Window Grouping

2.5 Related Works

3 A Configurable Transformer-based Anomaly Detection Approach

3.1 Problem Formulation

3.2 Log Parsing and Log Embedding

3.3 Positional & Temporal Encoding

3.4 Model Structure

3.5 Supervised Binary Classification

4 Experimental Setup

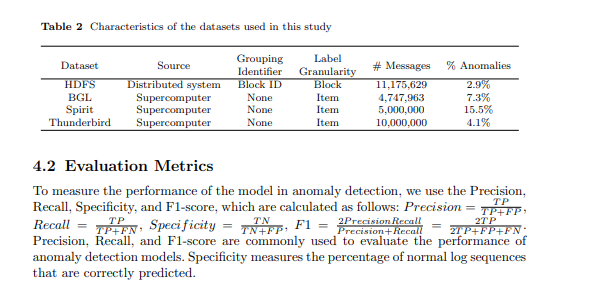

4.1 Datasets

4.2 Evaluation Metrics

4.3 Generating Log Sequences of Varying Lengths

4.4 Implementation Details and Experimental Environment

5 Experimental Results

5.1 RQ1: How does our proposed anomaly detection model perform compared to the baselines?

5.2 RQ2: How much does the sequential and temporal information within log sequences affect anomaly detection?

5.3 RQ3: How much do the different types of information individually contribute to anomaly detection?

6 Discussion

7 Threats to validity

8 Conclusions and References

\

4 Experimental Setup

4.1 Datasets We evaluate our proposed approach and conduct experiments with four commonlyused public datasets: HDFS [8], Blue Gene/L (BGL), Spirit, and Thunderbird [32]. These datasets are commonly used in existing studies [1, 5, 12]. The HDFS dataset [8] is derived from the Amazon EC2 platform. The dataset comprises over 11 million log events, each linked to a block ID. This block ID allows us to partition the log data into sessions. The annotations are block-wise: each session is labeled as either normal or abnormal. In total, there are 575,061 log sessions, with 16,838 (2.9%) identified as anomalies. The BGL, Spirit, and Thunderbird datasets are recorded from supercomputer systems, from which they are named. Different from the HDFS dataset, all these datasets have log item-wise annotation. However, there is no block ID or other identifier to group the log items into sequences. The BGL dataset is recorded with a time span of 215 days, containing 4,747,963 log items, where 348,460 (7.3%) are labeled as anomalies. As the Spirit and Thunderbird datasets each contain more than 200 million log items, which is too large to process, we use subsets of 5 million and 10 million log items, respectively, as per the practices of previous works [7, 11, 15]. We split the datasets into an 80% training set and a 20% test set. For the HDFS dataset, we randomly shuffle the sessions to perform dataset splitting. For the remaining datasets, we divide them in accordance with the chronological order of logs. The summarised properties of datasets utilized in the evaluation and experiment of our study are presented in Table 2.

\

4.3 Generating Log Sequences of Varying Lengths

Except for the HDFS dataset, which has a block ID to group the logs into sequences, other datasets employed by our study have no identifier to group or split the whole log sequence into sub-sequences. In practice, the logs produced by systems and applications do not adhere to a fixed rate of generation. Using fixed-window or fixed-time grouping with a sliding window fails to adequately accommodate the variability in log generation and thus may lead to inaccurate detection of anomalies in real scenarios. Moreover, according to previous studies [1, 7, 15], the best grouping setting varies depending on the dataset, and these settings can significantly influence the performance of the anomaly detection model, making it challenging to compare the effectiveness of different anomaly detection methods. Therefore, we use a method to generate log sequences with varying lengths and utilize these sequences to train the model within our anomaly detection framework. In the process of log sequence generation, we determined specific parameters, including minimum and maximum sequence lengths, as well as a designated step size. The step size is used to control the interval of the first log events in log sequences. The length of each log sequence is randomly generated in the range of the minimum and the maximum length. We assume the log sequence of the minimum length can offer a minimum context for a possible anomaly. The step size controls the overlaps of sequences. The maximum length affects the number of parameters in the model, and step size decides the amount of samples in the dataset. They should be aligned with the data distribution and computational resources available. In the experiments conducted in this study, we set the minimum length as 128, the maximum length as 512, and the step size as 64 for the datasets without a grouping identifier.

\ 4.4 Implementation Details and Experimental Environment

In our experiments, the proposed transformer-based anomaly detection model has two layers of the transformer encoder. The number of attention heads is 12, and the dimension of the feedforward network layer within each transformer block is set to 2048. We use AdamW with an initial learning rate of 5e-4 as the optimization algorithm and employ the OneCycleLR learning rate scheduler to enable a better convergence. We selected these hyperparameters following standard practices while also considering computational efficiency. Our implementation is based on Python 3.11 and PyTorch 2.2.1. All the experiments are run on a high-performance computing (HPC) system. We use a computational node equipped with an Intel Gold 6148 Skylake @ 2.4 GHz CPU, 16GB RAM and an NVIDIA V100 GPU to run our experiments.

:::info Authors:

- Xingfang Wu

- Heng Li

- Foutse Khomh

:::

:::info This paper is available on arxiv under CC by 4.0 Deed (Attribution 4.0 International) license.

:::

\

You May Also Like

TrendX Taps Trusta AI to Develop Safer and Smarter Web3 Network

Nvidia wants to boost H200 chip production to appease China